As entrepreneurs spark change, Africa’s electricity future is getting brighter.

Women working on solar lighting circuit boards.

Photo Credit: UN Women/Gaganjit Singh

With the blessing of global institutions increasingly worried by the prospect of climate change, entrepreneurs are hacking out a small-scale, low-carbon path to universal African electrification.

What’s encouraging them is the enthusiasm with which mobile phones have been taken up by many Africans and the new innovations and opportunities that this has opened up; the success of undersea fibre-optic broadband cables, the possibilities that this is opening up.

In Soy, in rural Western Kenya, some 280 km from Nairobi, as long as the sun keeps shining, Mark Kragh’s audience of young farmers is completely electrified. Turning sunlight into free electricity is a life changer.

“They’ve listened and learned like nobody I’ve taught before,” says Kragh who runs a solar panel business, KnowYourPlanet, in London. “They took notes, they figured out my diagrams. And within four hours, the first phone was charging away.”

Kragh’s solar master classes teach how to make solar phone chargers. These sell for 700 shillings (just over $8) each. There’s likely to be a ready market for them in Soy, says Kragh. It only takes 70 charges for the charger to pay for itself.

Access to electricity for Soy’s residents used to be a luxury. Now, with the advent of mobile phones, it’s turned into an expensive necessity. When everyone uses a phone, it’s difficult to opt out.

However, few people have electricity at home. With incomes in Soy hovering around the dollar a week mark, getting plugged into the national grid isn’t an option for most.

Charging a mobile phone at a shop or a phone kiosk costs around ten shillings (12 US cents) — prohibitively expensive. And there’s the cost of not working when trekking to the shop as well — a round trip of 10 kilometres for some of Kragh’s farmers.

Fresh from building miniature power stations with his students, the solar entrepreneur says: “The thing is that they’re really motivated to learn.”

Electric Innovations

In Silicon Valley and New York and London, tech investors with deep pockets are ready to consider innovative schemes designed to dent Africa’s electricity deficit. If this lays the foundation for new African businesses, a new culture of grass-roots entrepreneurialism, then that’s all for the good as well.

Leading social enterprises in this burgeoning sector include Solaraid which installs solar panels in schools and community centres across East and Southern Africa. Set up by Jeremy Leggett, the London-based company gives out small loans to African entrepreneurs so that they can get into the business of selling its products.

Founded by an American former investment banker, Katerine Lucey, SolarSister also uses micro-financing to fund small businesses. It creates “woman-centered” solar sales networks across rural Africa, in Uganda and Rwanda mainly, which sell its solar lamps.

Based in Kenya, backed by the World Bank, ToughStuff produces solar-powered products, lamps, solar panels, phone chargers, aimed at low-income Africans.

Founded by Ned Tozun and Sam Goldman, Stanford MBA graduates, based in San Franciso, d.light provides clean and affordable solar alternatives to kerosene lamps.

Leapfrogging

At the level of the UN or the World Bank, the hope is that low-income countries can miss out on the 20th Century, on electricity generation that’s dependent on fossil fuels, and instead develop low-carbon, decentralised schemes.

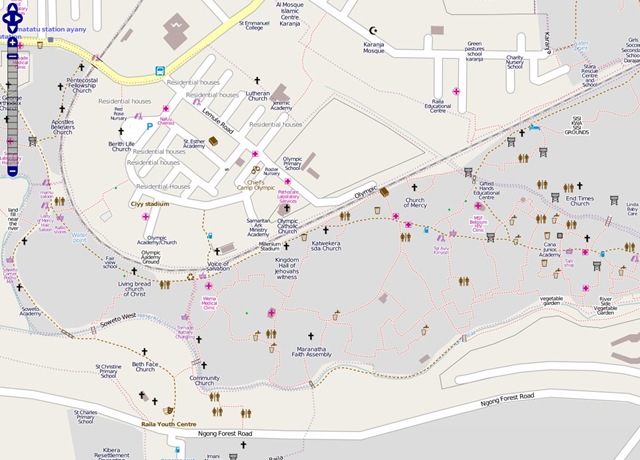

“The same leapfrogging happened with phones, when many places skipped landlines and went straight to mobile,” says Ken Banks, developer of FrontlineSMS, the free text-messaging software for Africa-based NGOs. “Perhaps the new model for Africa’s power is also very different, then — localised grids using renewable energies.”

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), a US-based industry body, predicts that what may emerge from these innovations is a meshing of grids with real-time performance data, an African “IntelliGrid” — a wireless information network binding together a continent-wide power system.

Such a smart grid would funnel together different sources of energy: centrally produced electricity, from traditional, hydro and nuclear power stations, combined with power coming from local micro grids and generated by renewables such as solar energy.

Constantly monitoring itself, the IntelliGrid would take steps to counteract any power disturbances. Power outages would become a distant memory, as ancient as needing an operator to place a telephone call.

Current Realities

At the moment, of course, Africa’s electricity supply is far from this. Count the backup generators in any five-star hotel, in any large manufacturing company.

In hard, economic terms, what counts most when judging any electricity supply is its reliability, argue Thomas Barnebeck Andersen and Carl-Johan Dalgaard, professors of economics at the Universities of Southern Denmark and Copenhagen.

“A patchy service is an improvement over no service, of course,” says Andersen. “But policy makers shouldn’t think that once a power grid is up-and-running, that this is enough in itself.”

When power gets turned off regularly, businesses end up having to cough up. Unlike their better connected competitors, they find themselves forced to invest in expensive generators. Computers are sensitive to even small power disturbances: surge protectors add to business costs. Computers go wrong more often: there’s less investment in IT, less readiness to innovate. All this harms economic growth over the medium term.

Here’s a counterfactual. What would happen to Africa’s economic growth if all African countries were to experience South Africa’s power quality? Instead of, say, 10.5 power outages during a typical month, if the number went down to two: what would that do for Africa’s growth figures?

Anderson and Dalgaard’s research suggests that the average annual real GDP per capita growth rate would increase by two percentage points. In other words, countries like Ghana and the DRC would find themselves growing as fast as China. “This is how important a reliable power supply is,” says Andersen.

A version of this appears in the May issue of Bspirit, the Brussels Airlines magazine.