By developing its developers, Africa’s tech sector hopes to go from ping to kerching.

Time was when African software developers didn’t register on Silicon Valley’s radar. No undersea fibre optic cables meant that there wasn’t much of a digital infrastructure in most of sub-Saharan Africa and so accessing and developing its software market was tough work.

These days, with access getting easier, the African blip on the Silicon Valley screen is starting to ping somewhat louder: the world’s biggest technology companies can’t get enough of the right kind of African ideas.

Seeking solutions to African needs, the kind not generally grokked by Silicon Valley VCs, companies like Google and Nokia are working hard to encourage African developers.

They go into schools and universities. They set up apps markets. They help with marketing. They sponsor conferences. But the most obvious way, the one which gets the most attention, is via the kerching and bling of the apps challenge.

Going app?

Photo Credit: AMagill

Typically, the challenge is to design a new app in exchange for a small cash prize. With the announcement of the competition, marketing departments go into overdrive. Blogs posts and tech events show off the competing apps. Finally, there’s an impressive award-giving evening with pitches and backslapping and toasts to Africa’s tech potential.

When it works, it’s great. Developers are forced to consider what the outside tech world wants. The companies get a sense of what the developers can deliver.

However, there’s a feeling among developers, voiced across blogs and net forums, that this apps ride stops somewhere short of Silicon Valley. You meet the app challenge, you take part in the competitions, get judged by tech experts and then what? Isn’t it the case that big tech companies are likely to spin off the best apps and develop them in-house?

It’s true that young developers can end up giving away their work for not much, says Ken Banks, developer of FrontlineSMS, the free text-messaging software for Africa-based NGOs, and a veteran observer of the African tech scene. “The suspicion is that competitions like these, coming at the developers left, right and centre, are just a cheap way of scooping up the most potentially lucrative new ideas.”

Broadly speaking

Photo Credit: liewcf

The current excitement about Africa’s tech prospects is triggered by the ring of the cash register. The business analysts say that where there’s broadband in Africa, there’s new business. With the new undersea cables rapidly increasing broadband capacity, the economic growth that Africa has seen over the past five or so years is likely to continue.

As in Silicon Valley’s dotcom era, first mover-advantage mania rules among the big tech companies: the company which gets its platform, its killer apps, its tech ecosystem into place first, wins Africa – or so the theory goes.

In order to do this, an entrepreneurial culture needs to be created among Africa’s tech whiz kids.

Among Silicon Valley techies, there’s the perception that a potentially good cultural fit exists between Africa and global tech. Although it’s easy to over romanticise this, Africa’s culture is one of innovation, of make do and mend. Out of necessity. And this fits nicely into the tech world’s hacker ethos, the idea that you take what’s around you and hack it into something better.

And, of course, there’s the wider issue of African knowledge. African developers understand African needs in a way outsiders just can’t.

For example, with computers priced out of the reach of many Africans, the mobile phone became the key tech device. Unlike their counterparts in the West, African developers are mobile net natives, wise to its opportunities and limitations.

The key question, then? How best can business harness this African potential? The answer? Build an entrepreneurial tech community.

“Someone working at Google in San Francisco is going to struggle to understand how a service needs to run in rural Kenya,” says Banks. “By providing help and resources to a rural Kenyan developer, however, Google can tap local knowledge and build exactly what’s needed.”

Community spirit

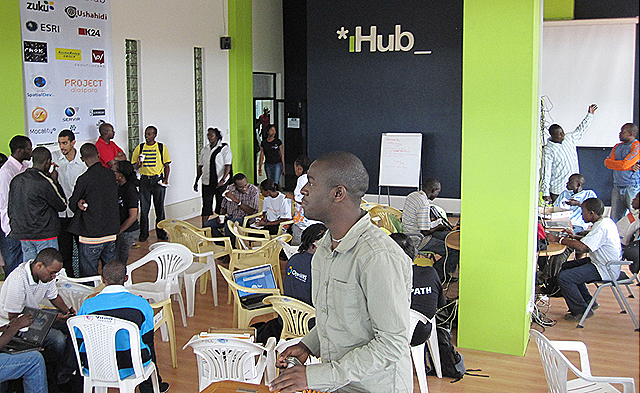

Photo Credit: WhiteAfrican

Taking place on 14 to 15 June in Nairobi, Kenya, Pivot 25 is a step towards the kind of ideas chain Banks describes. Open to east Africa’s mobile startups, it’s an apps challenge with a difference – it’s as much about creating community as kerching. Yes, there are the judges and the pitches and the cash prizes and the networking opportunities, the chances to click with potential investors.

What makes Pivot 25 interesting, however, is that it’s based within an innovation hub, a physical space for developers, which in turn is part of a wider African tech community.

Created by the team behind the award-winning Ushahidi software, the iHub acts as a space for events held by and for the local software developer community. It “incubates” young coders: it gives them somewhere to hang out and swap ideas and learn how to collaborate on projects.

The iHub is part of the new Afrilabs Association, a network of innovation hubs across sub-Saharan Africa. Run by expats and children of the African Diaspora, techies all, they aim to inject a Silicon Valley entrepreneurial vibe into local tech cultures.

What innovation hubs like Afrilabs will do is encourage the survival of the fittest apps while ensuring that developers get to develop too, says Banks.

“The best ideas will naturally rise to the surface, but people will have the chance to keep hold of their ideas and not sell out cheaply. Any success will be because of the merit of the idea rather than because a panel of experts hyped it.”

Jon Gosier, co-founder of Hive Colab, an Afrilabs hub in Kampala, Uganda, says that what he and the other Afrilab hubs are building on is “local creative surplus”, the knowledge peculiar to Africa which Africans have and which could be used to drive innovation.

The business models and focus of the hubs vary: incubating talent, coworking or even just creating a community space for local hackers.

What the hubs have in common is access to funds and “pools of talent on the ground”, says Gosier. Operating across boarders, they bring the two together.

“So instead of an investor worrying about the nuances of doing business in so many different countries, we can take on some of that responsibility and let the investor and entrepreneur focus on building their businesses.”

Find out more:

The iHub, Kenya

ActivSpaces, Cameroon

Hive Colab, Uganda

Nailab, Kenya

Banta Labs, Senegal

A version of this appears in the May issue of Bspirit, the Brussels Airlines magazine.